Abbiamo sempre scritto sui muri, spesso affidando loro i nostri pensieri più profondi. Solo nell’Ottocento, quando il passato si è trasformato per noi in una “una terra straniera”, abbiamo cominciato a condannare quelle scritte. E a chiamarle graffiti. Eppure, come ha scritto Michael Press su Hyperallergic

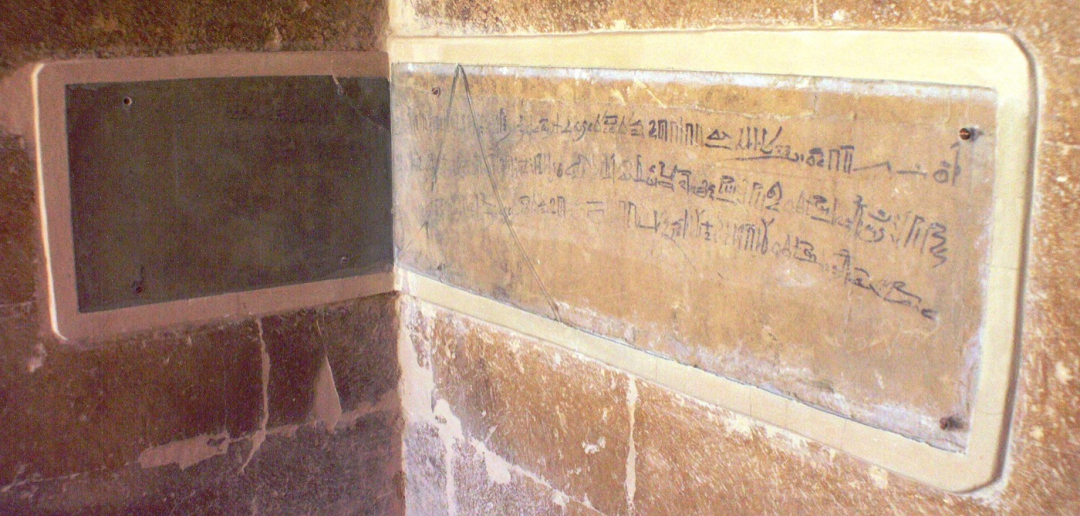

Graffiti gives us a wealth of information about human history, but it does so much more than that. It provides a vivid way to think about our relationship to the past, how people long ago were much like us and yet separated from us by a giant gulf at the same time. People in the past often had very different attitudes toward things like informal writing on walls, and often put such writing to very different uses. Yet, for them, as for us, graffiti often shares the same peculiar combination of a mundane act with striving for immortality, for something after or beyond our own lives. Phenomena like travelers leaving graffiti at the sites they visit seem to persist throughout human history. The 3,000-year-old graffiti at Saqqara, remarkably enough, was left at a time when the Step Pyramid was already ancient. Perhaps more than anything else, graffiti provides us with a sense of wonder — at human existence in all of its contradictions.

I graffiti sono noi, la nostra storia. Lasciano ai posteri la possibilità di penetrare la nostra anima. Impariamo a conoscerli meglio. Leggete l’articolo qui: The Clandestine Cultural Knowledge of Ancient Graffiti

0 commenti